This is the second coursework for semester one of the Machine Learning Practical (MLP) course I took as part of my MSc Artificial Intelligence at the University of Edinburgh. For this coursework, I experimented with many different convolutional neural network architectures, and found several improvements over the baseline for recognizing handwritten letters and numbers in the EMNIST dataset.

The implementation part was relatively low-level, using numpy and SciPy to implement convolutional and max pooling layers inside the MLP framework in Python.

For the experimentation part, we got $50 worth of free Google Cloud credits to train our models on GPUs this time, so I didn't have to fall asleep to the sound of my laptop fan spinning every night like I did for the first assignment. I explored different ways of broadening the network's receptive field as an input image progresses through to deeper layers. For explanations of the relevant concepts of striding, pooling layers, and dilations, see my report below. I tried to answer these two research questions:

- For different dimensionality reduction types, how does changing the network architecture in terms of number of kernels / feature maps per layer affect the network's performance in terms of accuracy and speed? Is it better to increase the number of feature maps as we progress to further layers, decrease it, or keep it the same?

- How do different architectures for dilations per layer and kernels per layer affect the network's performance in terms of speed and accuracy? Since the images are small, would lower dilations work better than the default two to five dilations per layer?

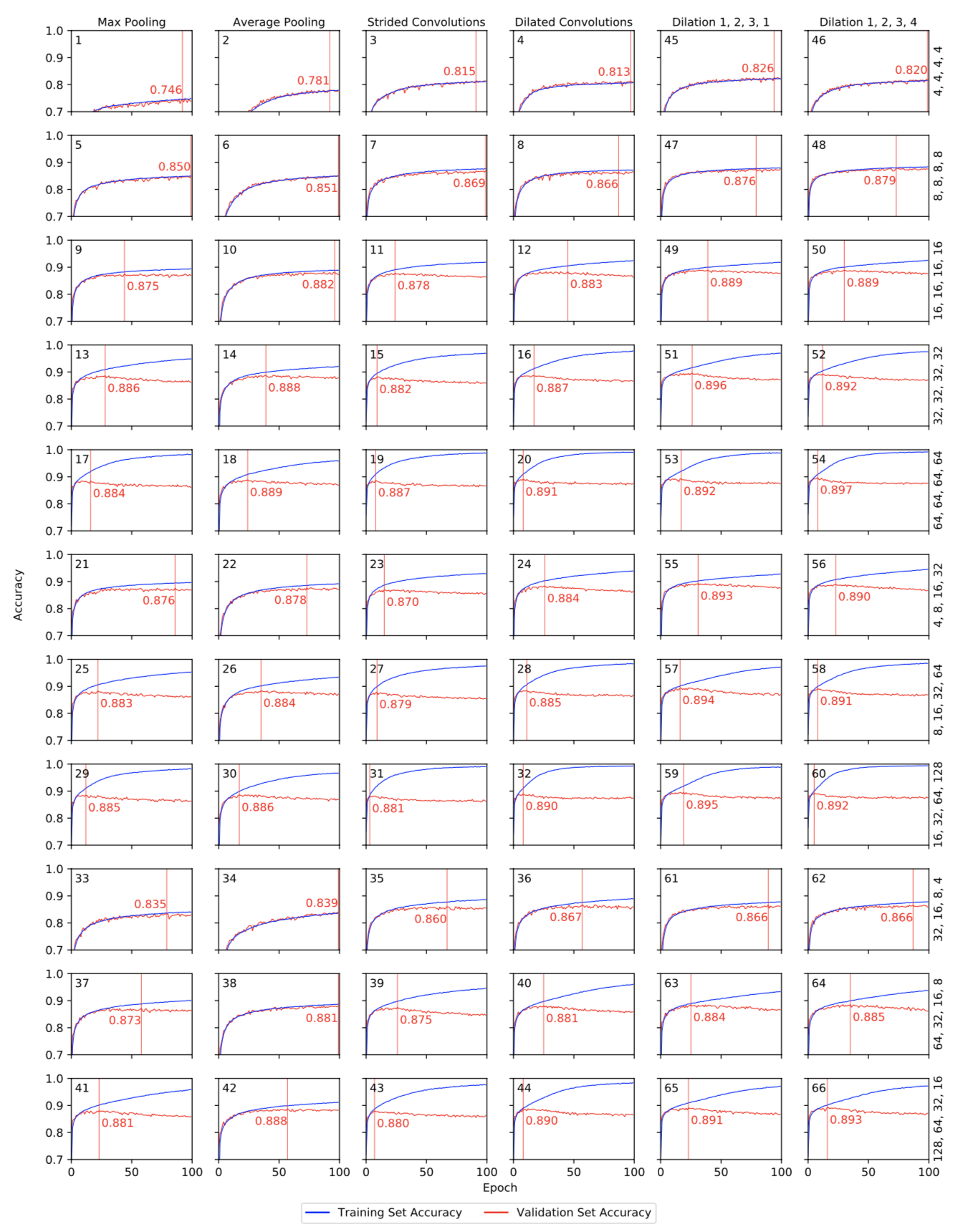

To answer these, I experimented with changing the architecture in terms of kernels per layer: keeping them constant per layer, increasing them with network depth, and decreasing them with network depth. I also experimented with different context broadening techniques: max pooling, average pooling, strided convolutions, and dilated convolutions with three different dilations-per-layer settings. This comes out to 66 different combinations to train, resulting the following (rather crazy) set of graphs:

Training (blue) and validation (red) curves for models 1 - 66, resulting from the experiments for research question 1 (first four columns) and research questino 2 (last two columns). The black number at the top left of each graph indicates the model ID. The red line indicates the epoch that reached the highest validation score; the red number indicates the highest validation score. Labels at the top indicate dimensionality reduction type; labels on the right indicate the architecture in terms of kernels per layer.

I concluded that for research question 1, although the baseline of having an equal number of kernels per layer yields the highest overall accuracy, models that increase their number of kernels per layer with layer depth perform better at small scales: with relatively short training time and a relatively low number of parameters to train, these models score higher in accuracy than models of similar scale. For research question 2, I concluded that smaller dilations perform better than the default dilations in the MLP framework.

For more details, see my full report below (or download it as PDF).

This coursework received quite a good grade; the biggest missing piece was that I should have analyzed my implementation in more detail, including estimating computational efficiency for my models and reporting training run times for my experiments.